Mick Jackson: I personally prefer films with deep social message

Written by Eva Csölleová, Vítek FormánekBritish born-American-based director Mick Jackson (4. 10. 1943) must be a fine man. When we wrote him after 11 years and asked him for autograph and request for interview, he replied with long personal letter and gave us happily his e-mail. We sent questions and he replied with 12 pages which is unheard of these days from film department people.

Growing-up in the grimness of the post-war period, amid the ruins and devastation of the Blitz bombings, the crushing austerity and food shortages

Tell us about your childhood and life in general in England suffering aftermath of WWII.

I was born in the suburbs of London. England, in 1943, in the middle of World War II. Growing-up in the grimness of the post-war period, amid the ruins and devastation of the Blitz bombings, the crushing austerity and food shortages, I took comfort in movies. In the small town that I grew up in, there were four large movie theatres – extravagant and opulent Art Deco “Picture Palaces” dating from the 1930s. There, in the darkness, I could escape from the misery of my real life into the seductive world of movies and storytelling. My family went to see films several times a week – I guess it was their way of escaping, too. But it was never

enough! On weekend mornings, I could go on my own to one of the biggest theatres, the State cinema, and for a few pennies, I could see even more movies. The projectionists would run old films – whatever they could pull out from their storage vault – old British war movies, American musicals and biblical epics, detective stories, gangster stories, film noir, everything under the sun. Inevitably, I started to absorb from all these viewings a sense of how it was done, how the language of film conjured stories, not just out of dialogue, but out of images, editing and the imaginative use of sound coupled with the emotional power of music. When I grew up in 50s and 60s and studied, I used to go to cinema by bus and watched a lot of films of Godard, Chabrol, Antonioni, Truffaut, Visconti, Fellini. It was magic.

How did you get to work for BBC, your journey wasn´t steady, was it?

For some strange and now forgotten reasons, I had decided that I would study science subjects so I was at Southampton University studying Electronics and heading for a life as a scientist. But the more I studied it and, at the same time, the more I was fired up by the movies I saw, the unhappier I got. It came to a head for me in 1965, just before I graduated. One night in the Student Union, I watched Ken Russell's BBC movie The Debussy Film on TV. Ken Russell's early work for the BBC was some of his best and boldest, and very provocative for its day. This effort was a film-within-a film about the French composer Claude Debussy and his troubled life I had not seen this kind of bravura risk-taking film-making before – and certainly not at a somewhat stuffy organization like the BBC. It caused a lot of outrage at the time but for me it was inspiring. I got my Electronics Degree a few weeks later and, putting that behind me forever, I applied to the University of Bristol. This was in 1965. Bristol had a Department of Drama and, among other things, it was one of the first real “film schools” in Britain. They accepted about a dozen post-graduates every year. I was the only scientist ever to apply, which was unusual and weird enough for them to accept me. In that year I got an exceptional grounding in film grammar and critical analysis, as well as a knowledge of English and European drama and the chance to make student films. From there, a year later, in 1966, I joined the BBC as a film editor. Within about a year, I was directing fact-based TV shows and shooting film documentaries. In the nine years I spent doing that, I learned a great deal about the world and most importantly, I learned much of what I needed about the art and craft of telling stories.

The 60´s were very revolutional all around the world. Did you have a social empathy and did you feel those vibes of changes and freedom, which came after tied up, post war years?

Yes, I grew up as a product of the 1960s and early 1970s – a time of great activism and desire for social change. So, yes, I protested outside the US Embassy in London against the Vietnam war and went on marches to decry the Apartheid of the South African government. But I also had fun. I jostled happily in the mosh at Pink Floyd's concert in Hyde Park, I saw Cream's final appearance at the Albert Hall and got sunburned at the Glastonbury Rock Festival. In my spare time, I made Pop Art paintings in acrylics in a style inspired by the English artist Peter Blake. I went to a lot of light-shows and experimental theatre and my then-wife and I made random “underground movies” by triple and quadruple exposures of 8mm film which we projected on the walls of our London flat while listening to Pink Floyd's Astronomy Domine on big headphones. Those were the good aspects of the era.

What were the bad ones?

Mostly I worried about nuclear war. In the early 60s, I'd listened with my fellow university students, gathered round a radio as the last minutes of the US Ultimatum to the USSR in the Cuban Missile Crisis ticked by. We all thought we would most likely be incinerated within the next few hours. Nuclear Armageddon seemed very close. In the end, Kruschev blinked first. The Russian ships carrying the missiles turned back and the threat of nuclear annihilation subsided. But it  never went away. Right after the end of World War II, Winston Churchill, the then-Prime Minister of Britain, secretly ordered the BBC, then the only broadcaster in the country, that the issue of nuclear war should never be mentioned – not even in serious discussions or documentaries. He knew from his scientific experts that there was no practical way in which a civilian population could be protected from the Bomb and he feared public panic and unrest. The prohibition lasted for nearly two decades, from the 1940s to the 1960s.

never went away. Right after the end of World War II, Winston Churchill, the then-Prime Minister of Britain, secretly ordered the BBC, then the only broadcaster in the country, that the issue of nuclear war should never be mentioned – not even in serious discussions or documentaries. He knew from his scientific experts that there was no practical way in which a civilian population could be protected from the Bomb and he feared public panic and unrest. The prohibition lasted for nearly two decades, from the 1940s to the 1960s.

In BBC nobody could talk about nuclear war topic till mid 80´s

![]()

So, does it mean that making a film about nuclear war was almost impossible in those days?

In the same year that I joined the BBC, a young film-maker called Peter Watkins, in defiance of the ban, persuaded the BBC to let him make what turned out to be a shockingly realistic documentary-style movie about a nuclear attack. It was called The War Game and it was never shown. The BBC, decided it was “too horrific for the medium of broadcasting” and it was banned. Watkins resigned in protest, angry and devastated, and never worked there again. I entered the organization, in 1966, just after this had happened, and the sense of shame was bitter and palpable everywhere. Many thought the BBC had been too weak and had let them down. It became a “no-go” area. No-one spoke about it again for two more decades– not until the mid - 1980s. By then, the Cold War had returned. Russia had invaded Afghanistan and shot down a Korean airliner. Reagan had called Russia “an evil empire” and put his “star wars” Strategic Defence Initiative in place, scaring the Russians - who were convinced it meant he was preparing to strike them first.

By then, also, I was just starting on my second marriage and we were both looking to have children. But my new wife and I were both fearful about the dangerous world they would be born into. It was that fear that prompted me to act. It wasn't exactly that I was pissed off, except by people who claimed a nuclear war was winnable”. It's more that I was terrified. Everyone was. Nuclear war seemed possible again. The anxiety was everywhere but, thanks to Churchill's ban, nobody really knew anything. That raised the question: How can you even start to think about something so far removed from your own experience when you have no adequate vocabulary to deal with it. Would it be just like World War II? The Blitz? Maybe we could survive it? Could we? Maybe? It defied the imagination. It was, literally “unthinkable!” “unimaginable” ! However, I am a fairly imaginative person and I thought, “maybe I could visualize it?

![]()

Could I imagine it for them? I am still a scientist, after all. I will research it. Maybe I can make a film that the BBC will feel they can transmit this time because it is “purely scientific. No politics. No passion. Just pure science.

I wanted to use so called Kuleshov effect. I'm sure you know about this, but anyway...In the early days of the Soviet Cinema, a theorist called Lev Kuleshov, who was trying to invent film grammar, noticed a curious effect of editing. He found that when he edited a shot of an expression-less human face followed by another image, whatever it was, the viewer immediately created a narrative in their head. For example, if the second image was a bowl of soup, then the

expressionless face was seen as registering “hunger”. If the image was of prison bars, then the face was longing for “freedom”, if it was a mother and baby, then the face was obviously expressing “wonder and kindness” and so on.

It was always the same face, but each time the viewer made a narrative in their head that connected the two images.

So, instead of showing horrific images, I edited random shots of ordinary people in the streets of London at several familiar locations intercut with powerful images of what a nuclear explosion near there would do to them. So, an old lady's face was followed by a slow-motion shot of flying glass tearing into the side of a pumpkin. Another innocent face was followed by a shot of meat in a butcher's-shop window charring and melting under extreme (millions of degrees) heat. I'm sure you can imagine the narrative that this editing suggested.

Almost at the same time as you made Threads, Nicholas Meyer made legendary The Day After, movie of almost identical topic. How did you like it?

Here's what happened at my end.

After making Guide to Armageddon, I realized that there was a longer, more explicit movie still to be made about nuclear war – not just about the physical effects of heat and blast and radiation, but about the psychological and societal after-effects on the survivors. I had read the research by the American psychologist Robert J. Lifton who had followed the long-term effects of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings on the “hibakusha” - those who survived the

atomic blasts. It was clear that the complete story could only be told through dramatic means, not just by special effects or suggestion. I would need a dramatist. In 1983, I approached Barry Hines, a novelist and screenwriter who lived in Sheffield, an industrial city in the heartland of England. He wrote about ordinary working-class people and their struggles with a great sense of empathy. He had written a much-admired film called Kes, about a solitary young working class boy who befriends a wild hawk – a Kestrel Falcon. (The film had been directed by Ken Loach.)

I went to see Barry in Sheffield and explained what I wanted to do. Create a set of believable, ordinary people and then a narrative that would subject them, without mercy, to all effects that the laws of physics and nuclear war would

expose them to. The story was to be told entirely from their point of view, there would be no overview, no Gods-eye-perspective, no maps or generals or politicians, just the world immediately around them as they struggled to survive.

We talked and came up with a central idea.

In a film about death, we would start and end with life. There would be an act of spontaneous and simple lovemaking and an unexpected pregnancy. That pregnant woman (Ruth) would carry her unborn child through the war and be forced to give birth – alone – in savage circumstances. We would follow that child (a girl, Jane) through the first thirteen years of her life, a post-nuclear world after the war.

From a casual and brutish rape, the 13-year-old Jane would also become pregnant and give birth. She would gasp in reaction to her first sight of the baby. We would not see it except in our imagination.

We were both determined to make the story as honest and true and unflinching as we possibly could. The times demanded no less.

I pitched it to the BBC, arguing for it forcibly. They gave their authorization to go ahead with one proviso. “Take your time, don't rush, talk to every expert you can, double-check every fact, make it unassailable, don't hold back, Get it right.”

That was virtually the only note I ever got from them. I continued to travel throughout the USA and Britain that year, taking to atomic scientists, nuclear strategists, doctors, psychologists, agronomists, meteorologists, investigative journalists........everyone I could find. Barry continued to write. We both went to observe training courses for those local government officials who would have to attempt to manage the aftermath. We were determined that this would be the definitive depiction of nuclear war. It would need to be so shocking it could only ever be done once. It couldn't become yet another genre of “disaster movie”, like The Poseidon Adventure or The Towering Inferno. It was too important.

When we were in pre-production, looking for Sheffield locations, we heard that ABC had made what sounded like a similar film independently of ours. This was The Day After. We were dumb-struck but heartened. The burning issue of our time was being addressed.

This may sound unconvincing but I seriously thought: “If they do it and they get it right, I should not make Threads. It should be a salutary lesson and it should only be done once. I will stop production.” This was actually feasible. I was the principal driving force going forward with Threads. If I pulled out, it would not get made. The only loss to the BBC would have been the cost of my year's salary and Barry's initial fee. So, we paused and waited to see what The Day After looked like.

Frankly, I was disappointed and sad. I know from all the accounts that Nick Meyer had started with all the same aims and grand intentions as me, and I do believe he did his very best to stick to them. But I also know the hell he went through because of the ABC censors and their Standards and Practices rules and all the compromises he had to make. For American television, it was a disturbing enough movie to make US audiences very uneasy and worried and I know it affected Reagan. But it was bland where it should have shocked. It was more in love with its special effects than with any terrible psychological scarring of its characters. They were noble and made speeches, they were played by movie stars and there was a musical score.

There were even spectacular crane shots that recalled Gone with the Wind. Yes, it was a bit scary but the end result was that it was a “TV Movie of the Week”. My worst fear was realized.

It's interesting to compare the hospital scenes in the two movies. In The Day After, all the lights are on and, in a smooth tracking shot, characters push neat gurneys through remarkably orderly corridors and make speeches. In Threads, there is chaos, the hospital is overrun, there is blood and shit on the floor and legs are being sawn off without anaesthetics.

The essential problem was The Day After was made in the wrong genre. An American made-for-TV Movie is unfortunately way too small and inappropriate a vessel to handle such an enormous subject.

I was more determined than ever to go ahead with Threads and to shoot it as roughly as possible. No well-known actors, no tracking shots, no music score, no spectacular effects. Only documentary-style hand-held camera, wind and silence. It would be unusual and terrifying enough to be in a category of its own, “sui generis”. You could not mistake it for a movie-of-the-week.

So, have you been satisfied with the result of your own movie?

In one way, yes. I wanted to give people who could not easily comprehend “what it would be like” a powerful set of images that would come into their heads every time a politician or think-tank expert (and there were many of them) spoke of concepts like a “winnable nuclear war”. My hope was that anyone who saw Threads, be they a President or just a man-in-the-street, would remember the melting milk-bottles, the cyclist up in a burning tree, the woman in the ruins cradling her dead baby, the rats and the maggots, the final scene and all the rest of the grim unsettling realities.

The American cable-TV mogul, Ted Turner, immediately saw there was a big difference between The Day After and Threads and he acquired and aired Threads on his cable TV station WTBS in Atlanta, so it was seen in the US. I know from his State Department aides that George Schultz, the US Secretary of State at the time, saw Threads and probably briefed Reagan about it. And Nick Meyer wrote that Reagan saw The Day After as well.

There was certainly a change in tone in Reagan's rhetoric afterwards. No more talk of Russia as an “evil empire” and some real progress on arms control talks.

In the days that followed the airing of Threads in the UK, the London Times published a cartoon on its front page. It showed two people reading a newspaper. The headline in the paper said “Reagan's Peace Speech” and one of

the people is asking the other, “Do you think he saw Threads?” My daughter Holly, was due to be born the day Threads aired in the UK, though the birth was actually delayed a few days. But in any case, it was a comforting

thought, that Threads might, in some small way, have made the world a slightly better place for her to be born into.

I have tried always to plunge into something new and unfamiliar for the very reason that it is unfamiliar and you are not sure that you can do it

The topics of your films are very versatile and different. How do you choose them?

I think you should always aim to direct something that challenges you, not something you instinctively know you can do because you have done it before. I have tried always to plunge into something new and unfamiliar for the very reason that it is unfamiliar and you are not sure that you can do it. The adrenaline flows easily. I think that fear is an under-rated factor in creativity and I embrace it. I love the exhilaration that comes from following, say, a serious drama by then making a comedy - or a political thriller followed by a romantic musical. It also makes you a moving target, difficult to classify. If you are known as being, for example, an “action director” then people will only send you action scripts for you to consider directing. If you are known for being open to everything, you get to see wonderfully unexpected scripts.

I am now effectively retired but, as a working director, I got sent many scripts for my consideration to direct and I spent countless long days on my deck reading through the piles. These came either from the studios themselves, or from independent producers or sometimes from my agent with a recommendation to look at it. Some already had leading actors attached to play in them, others were purely speculative, with no studio or actors attached to them.

But I didn't have a team of any kind, apart from my agent. I relied on my own intuition. This wasn't just a question of whether the script was good or bad – you can normally get a sense of that after reading the first dozen or so pages. It was more about asking questions like “is this engaging?” is this something in which I could use my own individual sensibilities to bring it to life in a unique way?” or “Is this so challenging that I have to dive right into it and see if I can pull it off?”

Sometimes even an indifferent script can nevertheless have a great story or idea in it that maybe, if it was worked on with a different writer, we could make it sing.

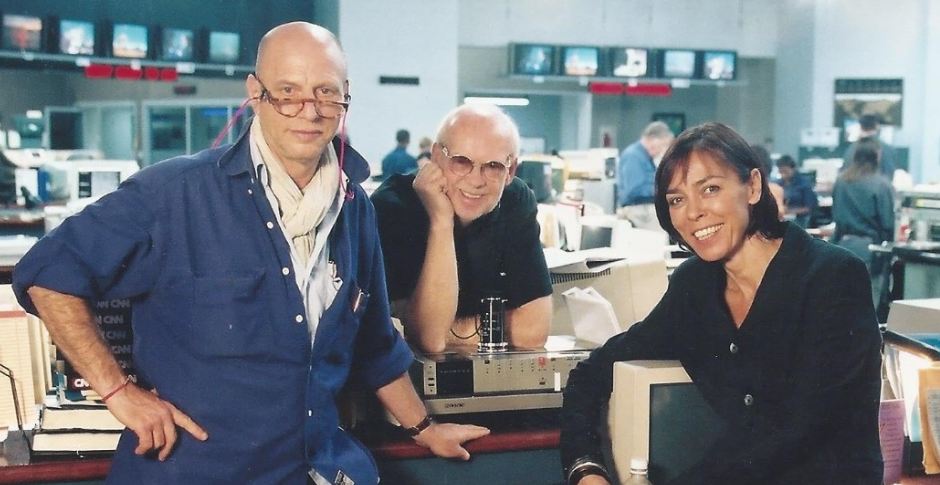

One example of this was Live from Baghdad - the story of the CNN producers Robert Wiener and Ingrid Formanek who reported from behind enemy lines in Baghdad during the first Gulf War in 1990. The initial script lacked a sense of journalistic momentum and HBO were not sure if they wanted to make it. However, I worked very closely with a different writer and he and I managed to turn them around.

One example: the original script had started very conventionally with wide establishing shots of Atlanta, then a few mid-shots and close-ups following

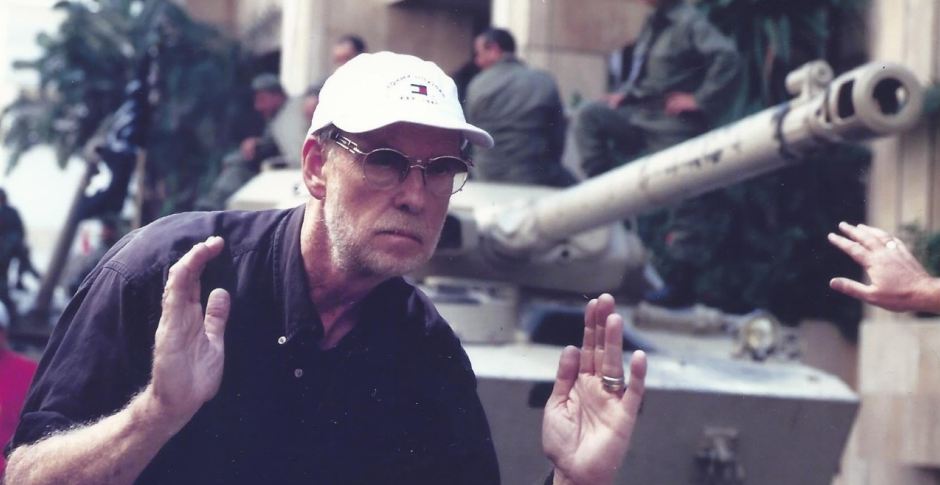

Robert Wiener to work as usual at his office at CNN. It wasn't very engaging. The re-written script started more surprisingly: We see the actor Kevin Bacon in a clip from a Hollywood movie of the time (Tremors). He's speaking in English but the camera tilts down to reveal Arabic subtitles. An Arab audience is watching the movie, sipping their Cokes and eating popcorn. Suddenly, the cinema screen starts to shake and explosions and gunfire are heard outside. Plaster falls from the ceiling of the theatre, as the audience flees in panic. Outside the cinema, an Iraqi tank crushes a BMW under its tracks. Tanks, fire and smoke are everywhere.

Women and kids run in terror. We are in Kuwait City in 1990 in the middle of the Iraqi invasion. NOW we cut to Robert Wiener (Michael Keaton) striding through the CNN studios in Atlanta, telling his boss “Baghdad is me!”

So, within the first 30 seconds, the film now had the inciting incident and the main character reacting to it. It was a movie with momentum and energy… For any director, movies are about collaboration. It can't be done alone. I have

always had close working relationships with writers, cinematographers and editors that persist through movie after movie. Threads could not have happened without the intense and sometimes explosive collaboration with the writer Barry Hines. We argued so passionately we almost came to blows, Yuri Nosenko only happened because the writer Stephen Davis and I had previously worked together on a movie biography of Andrei Sakharov. The relationship was already there. David Hare and I worked over many months on his script for Denial, sometimes line by line, even though he was in London and I was in Los Angeles. We spoke daily on the phone, we emailed, we sent revised scenes and drafts to each other. I flew to London for working sessions with him, he flew to Los Angeles for more work with me in Santa Monica, and we both met in New York for even more sessions.

The same is true for cinematographers. I have shot so many movies with the same three – Andrew Dunn, Theo van de Sande and Ivan Strasburg. When you have this close collaboration, work on the set moves smoothly and fluidly because we are in each-others' heads, thinking the same things, understanding each-others' sensibilities. And we are all life-long friends. This is the magic of movie-making.

What is more important for you to make a movie that makes profit or that brings some message to the viewers?

No question about this: Of course, it's nice if a movie is successful. It's also nice if, as a result, you get a higher fee for the next one. It's nice (but rare) if your contract gives you a decent share of the Box Office as well, and of course it's especially nice if you get rave reviews from the critics.

But this not the main reason we make movies.

We do it because we hope, in the darkness, that something flows from the heads and hearts of those who made the movie into the heads and hearts of every person sitting there watching the screen. It was true for me with Threads and with Denial and most notably with the HBO film Temple Grandin. The movie's a true story about an autistic woman whose condition helped her notice and understand animal behaviour, to the extent that she was able to design better and more humane slaughter houses and become a world expert on animal studies. (Not an easy pitch for a movie-maker to a studio, but HBO was up for it!)

The movie got very good reviews and over 50 awards and nominations - and HBO successfully sold it throughout the world.

But infinitely more gratifying than that were the many parents who came up to me after screenings and said: “Thank you for showing us at last what the world looks like to our own autistic child, For the first time in my life, we actually understood them – their pain and their joy.” There is no better reason for making a movie.

Why did you move to America? Britain had enough of you for pitching into ”wasp nest” with your movies or there was more in in the USA for you?

It happened initially by accident and through other people's actions, By the late 1980s I had directed three successful TV ventures in succession, Threads, The Race for the Double Helix and the political mini-series A Very British Coup. All of them won British Academy Awards among other prizes

and all were shown in the USA. I soon got a number of feature film offers from both Britain and the US. The British war film Memphis Belle for David

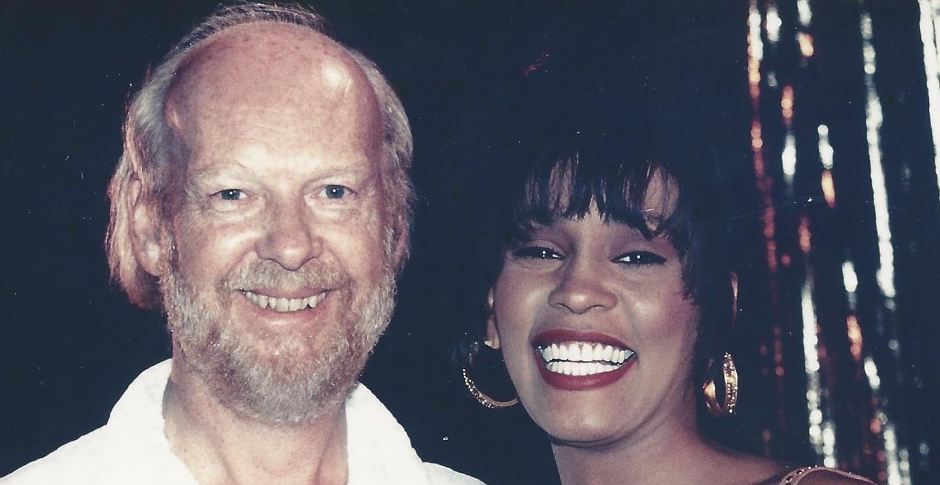

Puttnam fell through because of a timing problem. But Gary Oldman was already attached to star in Chattahoochee and told the producers he wanted me to direct him because of my work on A Very British Coup. So, I shot that in the US while still officially living in England. Then Steve Martin also saw Race for the Double Helix and A Very British Coup and asked for me to direct him in the comedy L.A.Story. Then finally Kevin Costner saw L.A.Story and asked for me to direct him in The Bodyguard with Whitney Houston. This was a fortunate sequence of breaks. By now, it was evident there would be work for me in the US – and my wife and family were getting tired of all the flying backwards and forwards between London and Los Angeles. My second daughter, Poppy, made the trip across the Atlantic at least four times as a baby before she was even one year old. So, as a family, we decided to move here. Every film presents different challenges of its own and I love the switch from a film with serious social issues to a romantic musical thriller. The change in each case can be bracing. It keeps you learning more about your craft and maybe uncovers new shades to your sensibilities. (Or not!) But my actual preference is for tackling more serious subjects when I can find them. Happily, The Bodyguard was successful at the box office and I got a few free drinks from Flight Attendants on planes as a result of it!

Directing films is about cooperation and team work. You can´t do it all alone

We touched the topic of film profits. Could you tell us more from your point of view?

This is a complicated area. Not many people make money even off a quite profitable movie. The calculations usually favour the studios. All their costs, for making the movie and marketing it, are deducted from the box office revenues first. Then, if you are an important player – like the producer or lead actor – you may get a share of the profit. The accounting is such that most often, there is little profit left for others to share. This was the case on The Bodyguard. Whitney Houston and I actually asked for a joint audit to see if we were owed anything, since the movie did quite well. The answer was essentially, “there won't be any profits till long after the end of the universe.” As it turned out, there were actually some profits declared – but not till 25 years later!

Why do people ignore films like Denial or they are not Box Office hits?

Not everyone ignores them. Money is not the only measure of a film's influence, and most often films like Denial are not made with a view to making a great deal of profit beyond breaking even. But they do reach a target audience and they do enter the culture. Even people who didn't see the movie now at least get, from those who did, some inkling of Irving's racist deceptions.

What is your view of David Irving?

I think that is clear from Denial – that he is someone who claims to be just a neutral “military historian”, but who is, in fact, an apologist for Adolf Hitler. He is also a fraudulent and racist falsifier of history, denying the very fact of the Holocaust itself. It is difficult to find any virtue in such a man, though apparently he is an affectionate father.

Have you ever visited Auschwitz?

I have, sadly, had to make four visits to Auschwitz in my life, not just for Denial in 2016 but also for one episode of The Ascent of Man back in 1973, which dealt with the subject of intolerance. It is always an experience that sears the soul. The visits are made all the more surreal and disturbing by the fact that, on the long drive from Krakow to Auschwitz, one passes a modern theme park and gaudy funfair close by. It is very hard to stomach that.

You mentioned, you are retired. Actually why did you quit directing?

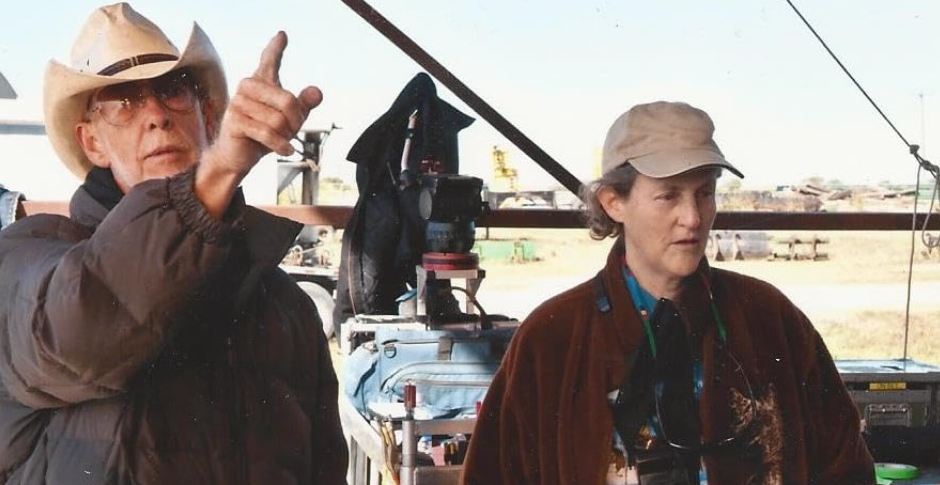

I also used to put a lot of my own energy and intensity into directing throughout the more than 50 years I was practicing it. I was quite well-known for never sitting down on the set; the director's chair was always clean and neat and empty and unused. I figured that while the crew was working I would set a good example by staying on my feet and staying focussed. It did seem to increase everybody's motivation and energy levels.

However, you can't sustain that level of intensity as the years take their toll on you, even by drinking huge amounts of coffee. (I think I routinely got through 15 to 20 cups a day.) I always tried to be "ON", to think on my feet and be one step ahead, ready with a Plan B or Plan C if Plan A ran into snags. In the end, I think I sensed myself gradually slowing down and I didn't want to do that. I know some other directors continue to work "still in harness" way into their 80s but I suspect the people around them have to make allowances, to plan sleep and rest-breaks for them and work a slower schedule. I never wanted to be that director.

I had a great working life, filled with joy and passion, and I continued on seemingly forever until it wasn't that any more. Then I stepped easily and swiftly away.

Thank you very much.

Photo, thanx: IMDb