Heather Kessinger: Making photos was very isolating thing

Written by Eva Csölleová, Vítek FormánekWe have never heard the name of this photographer and director before Febiofest started. But we got interested how she transferred from photographer to director so applied for making interview with her. When we met her, we addressed her wrongly as Henry Kissinger to which she smartly answered that one letter in her surname could make her more famous. We hit it off straight away and it was pleasant time to spend with this amazing lady.

Why did you choose photography as your job? Did you like looking at the world through lenses or you felt that you have sense to see something that others don´t?

Wow, you made your homework, that´s fantastic. Well, during the years I learnt that photography is for me and it allows me to do things which I love to do. I mean going to interesting places to various countries and with camera provides a kind of permission to enter the places. I don´t hide behind camera, but it is often the vehicle to enter places - otherwise I wouldn´t be able to do it.

Did you do something else to make money and you didn´t like it so you picked up the camera and started making photos or you studied photography?

Ha, ha, yes I did something else for long time before and did things traditional way since at that time I thought money equalleds freedom. So I worked in investment business doing analysis and research for various companies and it was awful, terrible. When I went to work in my working costume and met people in T-shirt and jeans I was almost jealous how free they appeared, and when I looked at people at my job who were in higher positions they looked completely uncomfortable and unhappy. I decided this was not for me and saved enough money, then quit and went to art school, which became great leveller for me. That was the best decision I have ever made. When I came from that school I had to figure out, how to do my art work and still pay my bills. I realised I have skills from my previous life but I don´ t have any longer desire to do it. So I took short time contracts, earned enough money, then quit and went to another part of the world, took photos and when I run out of money I took another short time shitty job. And in this way I was so fortunate that I got to the point when art took over.

If you are an artistic photographer and, say, like taking pictures of faces on the street, do you have to have written agreement from those unknown people, homeless people etc and if not could they sue you?

In my opinion you should have it, but lots of people don´t have it since these days everybody has a mobile phone to taking pictures is different than it used to be years ago and probably there isn´t enough attention paid to this, you never know where your photo ends up. I was working a lot in Northern India and took lots of pictures and it was mentioned to me that taking photos can be like entering someone´s soul, as if you were taking something that wasn´t yours. When I was doing still images and the person was central point of the photo and recognisable, I had to have his/her permission. But it´s been a long time since I have taken photographs of people since I am not a street photographer.

Did you focus on anything special like taking pictures of people, houses, nature, war or photographic collages or you basically photographed anything and then played up with in on computer and created something artistic?

For the first ten years I took photographs of environments and when I learnt my craft and felt comfortable in it, I started taking pictures of people and faces.

Conversation remains about who has the power to control the dialogue and we risk a world where individuals cannot speak their mind.

Last year, American female skier complained about calendar of naked women hanging in the office of the Czech timekeepers and saw it as a female exploitation and made big waves about that. How do you view these hypercorrect activists, obviously women get paid for taking nude photos for calendars and magazines so what is your view at that issue?

Oh, it´s tough one. I am not familiar with that specific instance you mention, but given your description I’m sure the skier was at once reacting to the objectification of women both in the image on the wall that she was forced to confront in that moment AND while she may not have noticed in the moment she has the experience of growing up in a world where the objectification of women throughout history is normalized – and she just wasn’t going to take it anymore. At least that’s what would have been going through my head if I were in her boots in that moment.

However, what I think you are asking me is really about the politicized climate we find ourselves in today – and with the ‘hypercorrect activists’ today I would agree that often times the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction. It gets difficult when we talk about hypercorrect political activism in the same breath as equality, as throughout history been injustice and inequalities that have brought us to the current climate. That the conversation remains about who has the power to control the dialogue and we risk a world where individuals cannot speak their mind – or their heart – especially if there is no harm intended. And we are in time where we risk the ability to have meaningful discourse between people who disagree and that is unfortunate. My father always repeated ‘do unto others as you would have others do unto you’ – if we all moved in the world with that we would certainly be better off.

I got a feel that when we sometimes talk to American artists especially, they are very careful what they say and it looks like they are afraid to say what they really feel not to have their career destroyed on internet. How do you view that?

People are going to say we are wrong no matter what we say or do, if they want to. My view is that artists should just do their work and not worry so much about what others think. I think everybody is entitled to say his/her own opinion, no matter what and if that viewpoint puts one in an unfavourable light then so be it. People who are hurtful to others should be called out, it is unfortunate when things are taken out of context and used just to incite others and may or may not be true – this is certainly a risk for anyone in the public eye. But this has always been a risk, it’s just more so now. Having an awareness that words and actions matter is appropriate, being fearful and having that fear impede creativity is not.

I needed to work with people around me since photography was very isolating.

When did you turn into film making? Taking pictures didn´t excite you anymore or you always knew that film making is your final destination and photography is just a middle step?

I am so honoured to have this conversation with you since no one really bothered to go to my history before and I have never been asked that question. I didn´t find photography boring at all and I still love it and even now I sometimes feel I want to go back to it since it´s nice to hold photography an actual photograph physically in your hand, or put it onto the wall which you can´t do with digital stuff. What I discovered with making photography was that it was a very isolating practice in the way that I did itg and I didn´t like working that way, I needed to work with people around me. When I turned into film I realized I can understand the visual language and can make images in the same way. So that was my entry point into cinematography. I realized one can´t make an entire film on one’s own (at least not a good one) and that building a team and collaboration solved both my desire to make a good film and resolved the uncomfortable isolation I was feeling as an artist.

What led you to film Shadow of Buddha?

I started going to North India with a professor from the San Francisco Art Institute, a fantastic photographer by the name of Linda Connor. You know, everybody was going to monastery photographing monks and the grand monasteries, it was all very traditional and I noted that no one took photos of the nuns. The nuns that I worked with were open – almost eager – to share their unique stories with me, that until this point no one had really stopped to listen to them. Now there have been many images and films made with Buddhist nuns at the centre, but back then there were very few if any and that would be a great subject for my first short film. And I admit that I was bit selfish in that as a first time filmmaker I knew that I needed to tell a new story. So when I returned to Ladakh to begin filming I had already developed friendships and trust back when I was a student and the nuns welcomed me back into their world.

Did you have a script?

No, I didn´t I just was filming but I had a notion of what I want to ask them. But trouble was that lots of my questions about how they feel came from my western perspective and didn´t make any sense to them. My observation was that the position of the nuns in society were subservient to the roles that monks held – and my western mind wanted to understand what they felt about that. I asked them questions that had no meaning for them so I had to change them. Life was difficult in a nunnery and as a woman in a village, comparison to external expectations of equality did not make any sense. I found that when I asked them if they would like to return in the next life as a man or as a woman this is when it got interesting. Most I asked this question of responded that they wanted to return as a man – not for reasons we might thinl – but because men had access to education and that is what everyone wanted, both men and women. However, the most meaningful responses came from the oldest nun I interviewed and the youngest, they both looked at me with a quisical expression and responded that it did not matter. I have tried to keep this in my heart ever since.

And you sent the film to the festivals and was refused?

I actually had a great response and the film was screened wide and far. What I did realize was that for the bigger commercial festivals I made exactly the wrong length of the film, which was 42 minutes. You either make short film up to 30 minutes or feature film but nobody wanted 42 minutes long film, it’s very hard to program. In the end I kept it as it was and did not change the story and screened it as much as possible and was happy with the critical approval it received. But I learned the lesson.

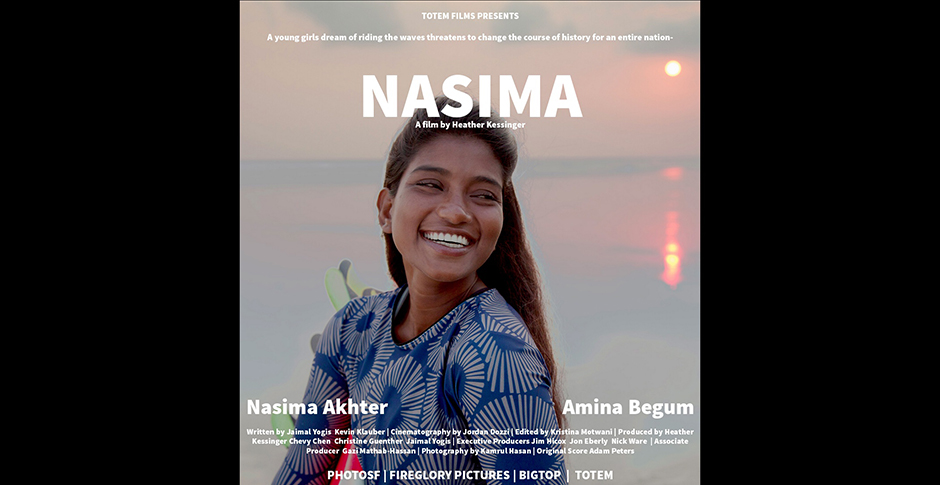

From nuns you moved to surfer in Bangladesh. Tell us about your new documentary The Most Fearless, please.

Well, this is a true story about Nasima Akhter who is the first female surfer in Bangladesh. In the very last moment of shooting it I realized that The Most Fearless is just an idea for the many many incredible stories about many many incredible people from different parts of the world and that is why we just changed the name of the film to be NASIMA.

And how did you get to it?

I finished Shadow of Buddha film and haven´t started new project yet. Friend of mine brought me the magazines and pointed at an article I had to read. I wasn´t in the mood of starting a new project so was very reluctant. Article was about surfing in Bangladesh and I was thinking ‘that’s crazy, no one surfs in Bangladesh’. But I was wrong and started to read the article after all. Bangladesh has the longest sand beach in the world, about 80 miles long, which is very unique and awesome for the surfers. What captured my attention in the article were two things: That they formed a club there and all were surfing from all backgrounds which doesn´t happen in that part of the world, people from different classes, from my observations, did not mix. Second thing was that when club started there were boys and girls together and after two years, only girl that left was Nasima. All of the other girls had dropped out because of abuse from the men in their lives and the community not accepting that girls too wanted to surf. In Bangladesh women do not swim in public. Little girls yes, but once they turn certain age, it´s no longer accepted. And I realised that there has to be something in Nasima, and that she must have a powerful story. I had never been to Bangladesh, knew nothing about it. I obtained address and contacted author of that article Jaimal Yogis and we started communicating. I found out that physically we were only five miles apart, World is small!!!!We met and he was really interested in someone picking up the story of the girls and he introduced me to the surf community. When I finally saw Nasima appear on my screen on a video call, I knew that she had something special in her and I knew I would soon me on my way to Bangladesh.

Right now I am drawn to make films about extraordinary life stories of various individuals.

Was it difficult to find money for such project or you worked on shoe string budget?

Three months later I put together a super small team and we flew to Bangladesh. We had very tight budget, got money from friends and family, we did crowdfunding and it took us seven years to make that film. We were lucky since when we shot enough material we showed it to one company that got interest. World premiere here in Prague.

Do you intend to step up to feature films one day or your mission is to film something appalling or extraordinary, show true human stories?

Right now I am drawn to make films about extraordinary life stories of various individuals. I have found that real life is often stranger and more compelling than fiction – and that what appears before me is often far beyond what I could have written.

Was or is it difficult to get to studios or companies and talk to proper people who would help you with your projects?

Yes, of course it was difficult, if not downright impossible most of the time! Just to get a response is better than what often can happen – which is no response at all. Even a straight up rejection would be preferred. But people are arrogant and don´t bother to react. But what keeps me going – what keeps most of us going – is that unexpected ‘yes’ from someone who gets what you are trying to do – that provides that necessary bit of encouragement or funding at just the right time. There are so many ways that film and media distribution and technology are evolving that hopefully there will be little need for the traditional gatekeepers and that good projects and good stories will more easily find their audience.

Thank you very much.

Photo, thank you: Heather Kessinger, Febiofest